The other day I was asked, certainly not for the first time, whether Christians may invest in the stock market.

Part of my job is to help Christians think through how biblical teaching applies in the nuts and bolts of daily life, so this is a very good question indeed. I've never written down my thoughts on this, and as the question recurs from time to time I thought it would be a help to jot things down.

There are lots more knowledgeable than me on this topic, and I'm sure there are books that are more thorough. If you've got a recommendation, please put it in the comments section at the bottom of this post. Nevertheless, I hope these thoughts will help you get started in your own thinking.

Disclaimer

First, two important disclaimers.

- The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

- I am not a financial adviser. This is an article on biblical ethics, not a general recommendation on how to invest money, and certainly not a personal recommendation that takes account of your own circumstances. Always do your own research, and obtain proper professional advice as necessary.

The Reason for the Question

Some Christians believe it would always be morally wrong to invest their personal money in the stock market. The usual reason for this is that it is confused with gambling.

Gambling is, I believe, morally wrong, provided it is defined carefully. I will define gambling as a game of chance, whereby people are invited to pay money for the chance to win either a larger cash payout than their stake or non-cash rewards of significant value. The "game" is set up so that, on the basis of probability, the promoter will receive more in stakes than they pay out in prizes. On the balance of probability, therefore, the promoter will make money and those who take part will lose money. The higher the stakes, and the more times the game is played, the more likely you will be to lose.

This therefore includes most casino activities, the National Lottery and equivalents, fixed odds betting terminals (which the government has, thankfully, recently legislated to restrict), and gambling machines such as fruit machines. On a smaller scale, it includes office sweepstakes, raffles and tombolas, prize draws to support a local charity, a "100 club", and penny arcade machines aimed at children. As a family, we don't take part in any of these. Our church does not hold any raffles at events. Although we urgently need funds for a new church hall, we will not be applying to the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Why is gambling wrong? That's beyond the scope of this post. In brief, the kinds of concerns include the social impact of all such schemes that affect the poorest members of society, compounded by the addictive nature of gambling, the motive of greed that such games tap, the desire to bypass either of the legitimate biblical routes to wealth (work and inheritance), and the poor stewardship of using one's money in a way that will do nothing other than deplete it over time.

By the way, if you're at your local school summer fete, and are offered raffle tickets, why not just give them some money but decline the ticket. Or why not decline the raffle ticket but then make sure your children have three extra goes on all the rides instead; that way, they have a better afternoon, and the money still gets raised.

So is the stock market any different? May Christians invest in the stock market?

Let me make a number of points

Framing the Question

First of all, let's make sure we've framed the question clearly.

- "May" is not the same as "should". That's to say, we are asking "May Christians invest in the stock market?", not "Should Christians invest in the stock market?". The question is whether it is morally wrong ever to do so. I am not making the case that there is an ethical compulsion ever to do so.

- If the conclusions is that Christians may do so, that does not mean that you may do so. In other words, there may be reasons why it would be wrong for you to invest in the stock market, even if those reasons don't apply to every Christian.

- Many Christians live week to week, with only just enough to live on. Indeed, James 2:5 says that God favours the poor, so you'll find more people for whom life is a day to day journey within the church than in society at large. God calls us to be stewards of all he entrusts to us, and to seek contentment as we trust for his provision, wherever that is relative to other people. Those who do not have the means to save money for the future should not do so. Instead, the priority needs to be to remain debt-free as far as is possible.

- Should you find yourself with more income than your immediate needs require, you may wish to save for the future. However you do not need to do so; you may instead decide to give money to meet the needs of others or to further the spread of the gospel. "Save" may be the wrong reflex, the first moment you find yourself with something to spare.

- Even should you decide to save your surplus income, the stock market may not be the right place for you to do so. Standard financial advice appears to be to keep at least 3 months' living expenses in accessible cash accounts before locking cash away for longer periods or investing in other, less liquid, assets such as shares. You may also have other known events on your horizon, such as a wedding or a child about to start university, that may make share-based investments the wrong choice for you.

- It's important this question is not seen as testing the validity of capitalism. The kingdom of God is bigger than all the "isms" and ideologies that people buy into. A true Christian view of money is never that we wholeheartedly embrace capitalism, socialism, communism, or any other secular system of thought. Instead, we allow the word of God to inform our thinking, and if we find ourselves running parallel to various other schools of thought at particular points, then so be it. This question is far more specific, and not simply "Is capitalism biblical?" in fresh clothing.

Answering the Question

- Saving is good. If God gives you enough to be able to set money aside, it is good to do so. (Note that there are two counterpoint to this: 1. Hoarding is bad - James 5:1-3. 2. We should trust God to provide for tomorrow and worry about today; the birds don't store away in barns.) That's because it's good to be able to leave an inheritance for your children and grandchildren (Proverbs 13:22).

- We should put our money to work. Jesus told a parable in Matthew 25:14-30, in which 3 servants were entrusted with their master's wealth why he went away for a while. The ones who were praised were those who put the money to work, and so made more from it.

- We need to be cautious here; the language of putting money to work is language within the realm of the parable; parables tell a story to teach truth, but the teaching point usually illustrated by the scene in the story. The parable of the lost sheep is not teaching about how to look after sheep, but is using a story about sheep to teach God's care for his people.

- So, here, the context is that the parable comes between the ten virgins (Matthew 25:1-13) and the sheep and goats (Matthew 25:31-46). The parable is thus about Jesus' future return as king, and the accounting he will demand from his servants.

- Nevertheless, we are stewards of all he has entrusted to us, and should put those things to work. This includes our money, so the principle that our money should work to achieve good ends, and so grow, is not an illegitimate application of the parable, when rightly understood in its context.

- Work is good, too. Titus 3:14 and 2 Thess 3:6-15 apply. So get a job.

- But business and enterprise is good. You may work for an employer. But those who employ you had to start somewhere, otherwise they wouldn't have work for others to do. So, if you have the skills to become a plumber, you could choose to work for yourself. You could pay to obtain the necessary qualifications and equipment, register as self-employed (or incorporate a small business), and work. To do this, you'd need to invest money you've saved up, in the hope that you'd then replace it and more as you work hard over the coming years.

- But what if you don't have the skills to be a plumber, but a school friend does. What if they want to start a plumbing business, but don't have enough savings of their own. You could enter partnership with them. They'll do the plumbing, but you'll chip in a quarter of their start-up costs. In return, you get a quarter of their profits. That would also be putting your money to good use. Obviously, you'd research carefully whether you believe them likely to succeed.

- If you did that, you've just invested your money in shares in a company. You would own one quarter of the shares in issue of your friend's plumbing business. Their little company wouldn't be a Plc, traded on any stock exchange, but that's a technicality. In fact it's a technicality that increases the risk somewhat, because your deal with your friend is not protected by legislation and regulation. But you've just invested in a company's shares, as a way of putting your money to work.

- So you could do the same thing with a public company.

- In fact, it's a little more complex than that. There are only two times when public companies let you invest fresh money into their business. The first is when they are starting up, a bit like your friend the plumber. This is called an "Initial Public Offering". The second is when the company needs a cash injection and issues new shares, and sometimes in these cases members of the public ("private investors", in industry speak) are able to take part.

- The rest of the time, you don't invest in shares by giving your money to a company. Instead, you invest in the secondary markets. That's to say, you end up buying somebody else's shares from them. But the principle is the same; you believe this to be a business worth investing in, so you'll relieve somebody else of their share of the business and so own a part of the business yourself. Where it gets more tricky is that the price you pay is not your proportion of the objective value of the business, but whatever price you and the seller decided was a fair exchange at the time. That complicates the transaction, but what you're basically doing is the same thing.

- There are ways to spread the risk. Instead of investing in one company, you could invest in several. There are ways to delegate the decision making. Instead of investing in several companies, you can invest in a fund. (There are three main types: Investment Trusts which are closed, Open Ended Investment Companies also known as mutual funds, and Exchange Traded Funds which have some of the features of each. This is not the place to explain the differences. Remember: Get advice if you need it.) These allow you to invest your money in a basket of companies. Some are "actively managed" which means a human fund manager takes a (hopefully small) cut of the money to make decisions about which companies to invest. Others are "passive" which means the decision is automatic, say investing in all 100 companies currently in the FTSE100 index.

- In other words there are different ways to invest in businesses. You can invest directly in companies you research for yourself, in which case you have to do your research carefully. You can use funds to spread your investment around, in which case they do the detailed research into the individual businesses, but you need to understand their approach and the precise risks they'll be taking. These are all ways of investing in a business that will put your money to work. None of it is without risk, so you have to decide how hands-on you wish to be and are able to be, and what risks suit your own investment amount and timescale.

- Investing in shares is harder to avoid than at first appears.

- Most people contribute to a pension, either at work or one they've set up themselves. Almost certainly, those pension contributions go into one or several funds of the kind just mentioned.

- Even if you don't, you probably have a bank account that pays you interest. To pay you the interest, the bank lends your money out to businesses, not so very different from the kind of investing you'd be trying to avoid. The difference is that they pay you a small rate of interest in return for shouldering the risks involved.

- All of which is to say: Unless you wish to put your cash in a safe at home, you invest in one way or another. All you have to decide is how directly or indirectly connected you wish to be to the decisions as to which businesses the money is invested in. You have least say with a bank account, more say using a mutual fund, and most say by picking individual shares.

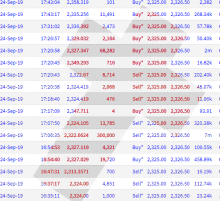

- The last thing to say is that investing is not trading. Everything I've said applies the principle that we should be good stewards of all God entrusts to us, which includes putting money to work in good and stable business opportunities. That suggests long-term investments in carefully chosen ways. Trading is another thing entirely; this is when people seek to buy in and out of companies so as to trade the ups and downs of the stock market, making money in the process. Most who try this lose, and it has far more in common with gambling. It is a totally different animal from the kind of responsible investing I'm talking about here.

In conclusion, I'd say that responsible, careful investing is very different from gambling. Yes, capital is at risk, for which reason care, research and proper advice is needed, and the risks should be considered when deciding how much to invest in different ways. A cash deposit account, where the initial capital is guaranteed, may well be the wisest choice for many people.

But Christians need to move away from the fear that any investing in company shares is, de facto, morally wrong. Instead, work out what is the wisest course of action for your particular circumstances, so as to be a good steward. Investing in shares (directly or indirectly) is one of the methods we have available to us as we seek to be good stewards of God's gifts.

Recent comments