500 years ago, William Tyndale lost his life in his campaign to give the English people one Bible in their own language. Today, we're spoilt for choice, with many excellent English translations of the Bible.

In any church where the Bible is read in public (which is, I hope, all of them), a decision has to be taken as to which to use. The right decision will vary from location to location. What reads as good English in one place will not sound quite right somewhere else.

In 2013, we took the decision to adopt the 2011 edition of the NIV (paid link), and I wrote a paper to lead our discussion of that. I'll reproduce it below, in the hope it may help others. Once again, let me repeat: Your mileage may vary.

The English Bible translation scene hasn't moved a lot since I wrote this. (The Christian Standard Bible (paid link) was published one year ago, an update to the 2003 Holman Christian Standard Bible. I have a number of friends who are very fond of the HCSB but felt it wouldn't work as a pew Bible; maybe the CSB is worth a look).

Why think about which Bible translation we use?

- We need something more legible / better paper / more durable than our current pew Bibles. Before buying these, it is worth thinking again about which translation we use.

- There’s another option today. We began using the English Standard Version (ESV) (paid link) in 2010. I’m convinced that, at the time, the ESV was the “best” (see below) English translation. The 3rd edition of the NIV (paid link) was published in 2011. I believe this is now a better choice for us.

We’re spoilt for choice today. Back in the 16th century, any Bible in English was a good thing!

What do we mean by “the best” translation?

- There is no perfect translation. Even between French and English.

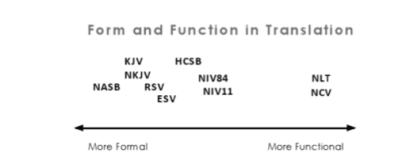

- Bible translations exist on a spectrum.

- At one end is “formal equivalence” –as far as possible each word in the original language is translated by an equivalent word in the modern language, so that the word has the same role in a sentence (same tense / mood / etc.). Word for word.

- At the other end is “functional equivalence” – as far as possible, you try to create the same meaning in the receptor language, even if that means using different grammatical structures. Translate thought for thought.

- No translation is all formal-equivalent or all functional-equivalent:

(I think I must have copied this diagram from a book somewhere and it helped our PCC think through the issues. I cannot now find the source, so if you own the copyright for this and would like me to remove the diagram, please contact me to let me know.)

- Which translation is “best” will depend on what it’s being used for. However we’re aiming for something that conveys the same meaning as the original (otherwise it doesn’t communicate accurately in English) without abandoning the sentence structure either (otherwise it is a new text, not a translation at all). We want a translation that is:

- Accurate: Turning original words into English, so that the message is the same

- Clear: What was written was clear to its original readers, so we want something we can understand. (That is not to say every concept is easily understood)

- Natural: Using expressions that a native English speaker would use, rather than going round the houses in a convoluted way

- Appropriate: … for what we will use it for. This is why different groups will use different translations. We want one that reads well from the front, can be studied in groups, can be studied in depth, doesn’t only make sense to graduates, etc.

Quick History of the NIV

- NT completed in 1973

- OT completed in 1978

- Revised in 1984 (second edition)

- 3rd edition released in 2011

Why was (is) the ESV so good?

- The 1984 NIV was very readable, but needlessly lost some of the original wording. Specifically:

- Lots of connecting words (“and”, “therefore”, “because”, etc.) unnecessarily removed.

- Also, the same word in the original was often translated differently into English.

- Sometimes this is the right thing to do, because one original word can carry different meanings. (Does “know” become savoir or connaitre in French?)

- However the NIV did this needlessly, only for stylistic variety.

- The result is that lots of significant details get missed in the 1984 NIV.

- For close study, people used to advocate the RSV (which was old with quaint English) or the NASB (focussed on formal equivalence that it was too wooden to read, especially read aloud.)

- The ESV broke new ground: a translation into good English that preserved the original to a much closer degree than the NIV ever had.

How does the 2011 NIV improve on the 1984 NIV?

- The translation committee specified the 3 reasons for any changes made to the 1984 NIV:

- Changes in English

- Genesis 19:9, “This fellow came here as an alien” becomes “This fellow came here as a foreigner”. The word “alien” means something different today than it did in 1984.

- Progress in scholarship

- Philippians 2:6, Jesus did not consider equality with God “something to be grasped” becomes “something to be used to his own advantage”, because we now know more about that particular Greek word.

- Concern for clarity

- In Matthew 1:16, “Jacob, the father of Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus” becomes “… of Mary, and Mary was the mother of Jesus”. The 1984 NIV could have left the impression that Jesus was physically descended from Joseph. The Greek pronoun “whom” is feminine which rules this out, so the 2011 NIV is clearer as to what the Greek is actually saying.

- Changes in English

How does the 2011 NIV improve on the ESV?

- The translators have also picked up on some of the criticisms of the 1984 NIV that led people to use the ESV. Consider Romans 1:15-16:

“I am so eager to preach the gospel … 16 I am not ashamed of the gospel.” (NIV 1984)

“I am eager to preach the gospel … 16 For I am not ashamed of the gospel.” (ESV)

“I am so eager to preach the gospel. … 16 For I am not ashamed of the gospel” (NIV 2011)- Paul’s point is precise, his lack of shame at the gospel is what makes him eager to preach it. We know this, because the little connecting word “for” begins verse 16; it indicates a cause, similar to the word “because”. “I am eager… because I am not ashamed”. Readers of the 1984 NIV would miss this, because the translators omitted the word “for”. The 2011 committee put it back.

- The translators have also managed to avoid some of the unnatural renderings in the ESV. For example, Ecclesiastes 7:16 says “be not overly righteous”. The NIV’s “Do not be over righteous” is much better English – it’s how we’d say it!

Gender-Neutral Language

- One specific improvement (under the heading of “changes in English”) is a recognition that masculine nouns and pronouns are now used less often to denote people in general.

- The exact rules by which the translators sought to work this out would take us into too much detail. It is harder than it looks to translate in this way. (When the original says “he”, it is more accurate to say “you” even though this is second-person, or “them” even though this is plural?).

- The cardinal rule was that wording in the original that was not gender-specific should not become gender-specific in English translation.

- What sets the 2011 NIV apart is how thoroughly they researched current English use of the related terms, to make sure their translation uses English that people today would use. They commissioned a study of a 4.4 billion-word bank of English use from around the world (spoken and written).

What about the King James?

The so-called “authorised version” or “King James” Bible of 1611 was commissioned by James 1 (in 1604) as a new translation from the original Hebrew and Greek. Its aim was to translate the Scriptures into the everyday English of its day. Many today love its language, but English has changed considerably, its translators did not have access to many of the Bible manuscripts we have today, and Hebrew and Greek scholarship has advanced.

What about the RSV / NRSV?

The RSV was published in 1952 as the first contender to be an alternative to the AV. It caused a few theological controversies in its time, with allegations that the theological bias of the translators had interfered with their ability to produce an accurate translation. Other than those disputed texts, it offers a word-for-word translation, but is consequently quite hard to read aloud.

The NRSV (new RSV) was published in 1989. It was the first major translation to adopt gender-neutral language, and also sought to update the RSV more generally.

Unfortunately, it shows its age in terms of language, and never quite managed to shake some of the RSV’s archaic use.

- Romans 1:15, above, becomes “Hence I am eager to preach the gospel.”

Its gender-neutral language was less carefully researched than the NIV, seeking to remove as many masculine terms as possible rather than seeking to translate accurately in line with modern English usage. 1 Timothy 2:5

“For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (NIV 1984)

“For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (ESV)

“For there is one God; there is also one mediator between God and humankind, Christ Jesus, himself human” (NRSV)

“For there is one God and one mediator between God and mankind, the man Christ Jesus” (NIV 2011)

Benefits of the NIV 2011 for us:

- The NIV is accurate, preserving the original word and sentence structures.

- The English is up to date and modern, clear and natural. It therefore also preserves the original meaning.

- It avoids gender-biased language that would jar for today’s hearers by meaning something different from what the original authors meant.

- Combining all of these advantages, it is therefore the most accessible translations across a range of education backgrounds, without gaining further accessibility by resorting to paraphrase.

- It is a catholic translation, translated by an international and interdenominational committee, rather than the product of a niche group with a theological axe to grind. (That is also true of all the translations discussed in this paper, but it deserves mention because it is a bare-minimum requirement).

- The 1984 NIV is widely read by many Christians. Amongst Christians who read the Bible at home, it’s the most widely used. The 2011 NIV has enough in common to feel familiar.

- The 1984 NIV is also widely used in published resources (daily Bible-reading notes, courses such as Christianity Explored, and as the translation cited in popular Christian books).

Recent comments